JAKARTA, Monday March 23, 10:19 AM (AFP) - US-based mining giant Freeport McMoRan is paying Indonesian troops to protect a large gold and copper mine in Papua, despite regulations requiring the military to hand over to police. The Arizona-based company said its local subsidiary paid "less than" 1.6 million dollars through wire transfers and cheques in 2008 to provide a "monthly allowance" to police and soldiers at and around the Grasberg mine.

JAKARTA, Monday March 23, 10:19 AM (AFP) - US-based mining giant Freeport McMoRan is paying Indonesian troops to protect a large gold and copper mine in Papua, despite regulations requiring the military to hand over to police. The Arizona-based company said its local subsidiary paid "less than" 1.6 million dollars through wire transfers and cheques in 2008 to provide a "monthly allowance" to police and soldiers at and around the Grasberg mine.The disclosure, made in response to questions from AFP, means the company continues to pay soldiers in contravention of a series of legal measures aimed at stopping military units working as paid protection, rights activists said. Grasberg sits on the world's largest gold and copper reserves, in a resource-rich but desperately poor region on the far eastern extreme of the Indonesian archipelago.

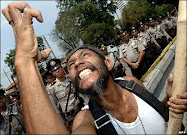

Pro-independence Papuan militants have waged a long-running insurgency against Indonesian rule in the province, and human rights monitors say Freeport's payments help fund military abuses against the local population. The latest attempt to cut the military out of protection payments -- part of broader democratic reforms -- came in a 2007 ministerial decree setting a six-month deadline for police to take over security of "vital national objects." The less-than-1.6-million in direct payments are part of eight million dollars Freeport paid in broader "support costs" for 1,850 police and soldiers protecting Grasberg last year, according to a company report filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission last month.

While most of the direct payments go to the police-led Amole task force at the mine, soldiers and police in surrounding areas are also receiving payments, Freeport spokesman Bill Collier said. "Although the bulk of our support is directed to supporting the Amole task force, we do provide some financial assistance to the police and military who are assigned to the general area surrounding our operations," Collier said. A 2005 report by rights group Global Witness alleged Freeport had paid hundreds of thousands of dollars directly to senior police and military officers between 2001 and 2003. The accusations are just one of many public relations headaches for Freeport, the largest single taxpayer to the Indonesian government. Claims of rights abuses and environmental damage at the mine are difficult to verify as Indonesia restricts travel by foreign journalists to Papua and Freeport seldom allows media into its area of operations. Freeport's Collier did not say if the 2008 transfers included large-scale payments -- in cash or in kind -- to senior officers. But he said the company's actions were within the law. However, Rafendi Djamin, coordinator of rights organisation the Human Rights Working Group, said the military payments were clearly illegal although payments to police, while ethically questionable, were permitted. "The safest thing to say for sure is they (payments to the military) are against the law.

They are against government regulations, ministerial as well as presidential decrees," Djamin said. Indonesian Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Purnomo Yusgiantoro declined a request to be interviewed on the legality of the payments. Global Witness campaigner Diarmid O'Sullivan said Freeport's disclosure of payments left unanswered questions over whether the company is paying large sums to senior officers. "Even now, the company still doesn't publish enough detail about its security payments to clearly confirm that this practice has stopped," O'Sullivan said. Also unanswered is just how many soldiers are being paid. Nyoman Suastra, the commander of the Amole task force officially assigned to guard the mine, told AFP there are 447 personnel in the task force, which includes some soldiers. Subtracting that number from the 1,850 police and military personnel Freeport acknowledges it paid last year, it means the company is paying 1,400 security personnel outside the mine, an unspecified number of them soldiers. "It is disturbing that Freeport still seems reluctant to answer the most important questions, which are: who in the security forces ends up with these allowances, how much money do they get and what is the legal basis for these payments?" O'Sullivan said.